Most of all, unsurprisingly, it’s tied to Jamaican people in Canada. Jamaicans came to Toronto in large numbers in the 50s and 60s, and since then have somewhat determined the tenor of Toronto’s black community while spreading their music to a multicultural fan base in Toronto, all the while maintaining possession of it.

Caribbean immigrants’ arrival in Toronto goes back well over 100 years but really started to pick up speed in the late 1950s when racist immigration policies were relaxed largely to permit immigration of commonwealth-resident nurses and household helpers. The Sheiks, arriving in the mid-60s, were the first Jamaican band to make a name for themselves here. They were well versed in American soul music and got gigs within Toronto’s thriving R&B scene at clubs like the Zanzibar and the Coq D’or.

The R&B scene had no appetite for contemporary Jamaican sounds like rock steady, so outside of those establishments, places like the W.I.F. and Caribbean Club, Club Jamaica and Club Trinidad were places to hear Jamaican music with fellow expats and curious locals from all walks of life (canned goods magnate Mr. Goudas spends considerable time in his autobiography talking about his experiences DJing Jamaican music at his 813 Club).

This era is surveyed magnificently in the first compilation of the six-volume Jamaica To Toronto series. One of the first major industry figures for reggae was the Sheiks’ manager Karl Mullings, who soon became a key advocate for Caribana, founded in 1967.

In the late 60s, a key figure in Toronto history arrived: Jackie Mittoo. Mittoo was the pianist of the legendary Skatalites ska band and had gone on to become the house bandleader for Jamaica’s foundationally important Studio One label, penning some of reggae’s most enduring instrumentals. In Canada, Mittoo set out to explore the Canadian music industry by seizing new opportunities like the establishment of new Canadian content rules. He released the album Wishbone in 1971 which was a curious brew of soul-pop, adaptations of some of his Studio One material and his quirky, rough-hewn vocals.

Another early LP from a talented Jamaican musician, Wayne McGhie and the Sounds Of Joy made a brief appearance around this time, only to achieve much greater acclaim decades later with its reissue in the Jamaica to Toronto series. Other early reggae artists of note in Toronto were The Webber Sisters, Leroy Brown, Glen Ricketts, and Stranger Cole, who ran a record shop in Kensington Market.

As the R&B scene started to fade away, a local musical identity asserted itself. By 1974, Summer Sounds recording studio was founded in Malton by Jerry Brown and boasted a sound comparable to the spacy, effects-laden records Lee Scratch Perry was releasing in Jamaica.

Shops abounded too: through the 70s and early 80s Eglinton West of the Allen Expressway featured record shops affiliated with prominent Jamaican record producers Duke Reid, Joe Gibbs and Prince Jammy (near the recently christened “Reggae Lane“). As with all record stores, these were vital places to socialize with other musicians and check out the latest sounds.

Cultural critic Dalton Higgins reminisced, “My father would come home from work every Friday and go buy 45s at Monica’s. I would mimic those energies in Grade 7 and 8, hanging out at the record store with my friends. And there were always elders and community leaders around.”

These shops also distributed local labels like Micron and Half Moon. Even Stompin’ Tom Connors’ Boot label released some reggae titles as part of a broader mandate to promote “folk music” from around the world.

By the mid-70s, Ishan People became the first homegrown band to gain renown as having a Canadian reggae sound. They recorded with Blood Sweat and Tears’ singer David Clayton Thomas and backed Bruce Cockburn’s huge hit “Wondering Where The Lions Are.” Earth Roots and Water and Chalawa also had distinct sounds.

Klive Walker, author of the essential reggae history Dubwise articulated the position of reggae from Canada within the larger Jamaican diaspora: “when diasporic reggae surfaced it had to contend with the international profile of Jamaican reggae, the reggae adventures of mainstream rock, pop, and rhythm and blues and the artists and the reggae musicians of Caribbean heritage who imitated Jamaican reggae.

Klive Walker, author of the essential reggae history Dubwise articulated the position of reggae from Canada within the larger Jamaican diaspora: “when diasporic reggae surfaced it had to contend with the international profile of Jamaican reggae, the reggae adventures of mainstream rock, pop, and rhythm and blues and the artists and the reggae musicians of Caribbean heritage who imitated Jamaican reggae.

Diasporic reggae justified its existence and produced its own major artists partly because it spoke to the everyday experiences, struggles, hopes and aspirations of young people of Caribbean heritage in cities like London (UK), Toronto or New York.”

A very different offshoot was brewing in the outer regions of Metro Toronto: the city’s first sound systems. Jonbronski, co-founder of CIUT’s hip hop touchstone The Master Plan Show, recalls: “Toronto, late 70s, early 80s sound crews had a very L.A. sound with heavy dose of reggae. Maceo, Killowatt, Sunshine, and City Crew (Buffalo NY) carried the swing, while more local crews got B-listed billing at parties. A lot of funk and funk instrumentals were played. No real rappers per se, but heads that know how to get the party right just by talking.”

A mix of American funk and a good dose of reggae remains a defining characteristic of Black music from Toronto over the decades. Throw in some London vibes and some pan-Caribbean flavour and that’s most of what G98.7FM plays today which sets it apart from American Urban radio such as Buffalo’s WBLK. This is how you “get the party right” in Toronto.

Though community newspapers like Share and Contrast had existed for years, it was difficult for reggae to break into the Canadian music and media industries. Leading stations like CHUM wanted nothing to do with homegrown reggae, even during Bob Marley’s most commercially successful years as he filled Maple Leaf Gardens.

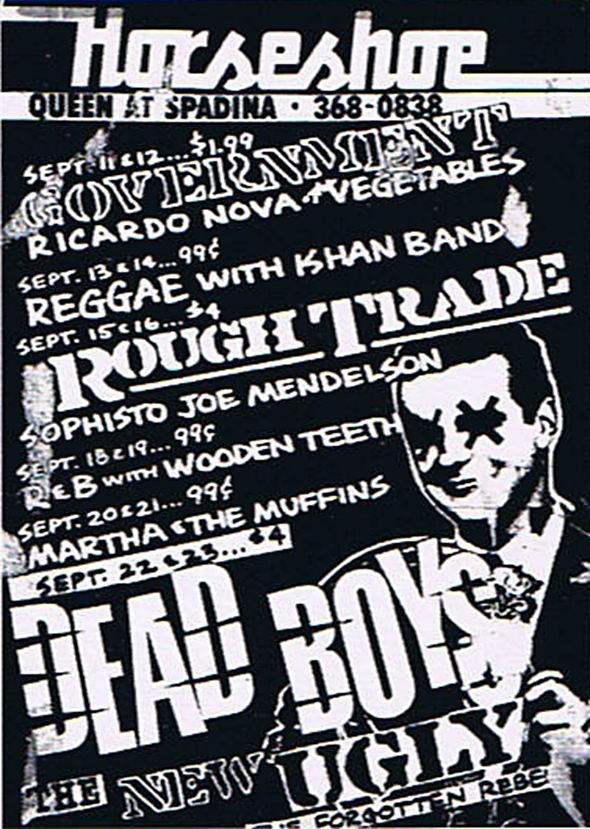

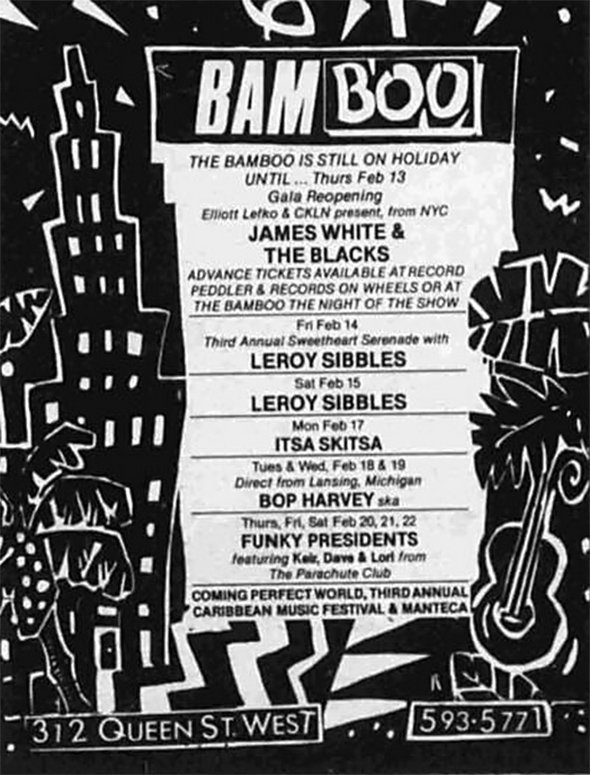

Fortunately, a big shift occurred as CKLN launched in 1982 (featuring David Kingston, partner to definitive dancehall photographer/author Beth Lesser) and CFNY’s Spirit of Radio era featured Deadly Hedley Jones‘ programming. On the print front, with NOW Magazine launching in 1983, all of the sudden there was new visibility to the burgeoning reggae-new wave culture clashes of Queen St. West at clubs like the Bamboo, the Rivoli and after-hours House of David.

Hybrid bands like V (a forerunner to the Parachute Club) interfaced with 20th Century Rebels andTruths and Rights to create a truly downtown Toronto sound. Leroy Sibbles, another Studio One luminary, became was the biggest star of this era and recorded for both Boot and Attic Records.

Dub poet Clifton Joseph recalls: “There was a scene going on Queen St. We were playing at those clubs, performing at different cultural events with a lot of different artists and Queen St. became in some ways our home. There was a whole sweltering rise of culture at the time. Queen St. became this place where there was a lot of cross pollination.”

Dub poet Clifton Joseph recalls: “There was a scene going on Queen St. We were playing at those clubs, performing at different cultural events with a lot of different artists and Queen St. became in some ways our home. There was a whole sweltering rise of culture at the time. Queen St. became this place where there was a lot of cross pollination.”

The 80s are still considered to be a high-water mark in reggae’s local and national visibility with groups like the Sattalites and Messenjah (from Kitchener, featuring involvement from veterans of 70s multicultural funk band Crack Of Dawn) and performers like Glen Ricketts, R Zee Jackson, and Chester Miller. However, Toronto’s most distinctive contribution to reggae perhaps ever was its strength in dub poetry, where instrumental reggae is the bedrock for socially conscious poetry.

Lillian Allen, Clifton Joseph, and their Dub Poets Collective were at the vanguard of a worldwide movement, hosting festivals and releasing challenging but hard-driving music. Allen’s Conditions Critical and Revolutionary Tea Party won Juno awards. While reggae in the UK hooked up with punk for rock against racism, these artists (particularly Allen, Adri Zhina Mandiela and Afua Cooper) advanced issues pertaining to feminism and black Canadian history as well.

Their international notoriety was indicative of a larger concept of Diasporic Music, to borrow the term of journalist/broadcaster Norman Otis Richmond, in which the distinctive rhythms of Jamaicans within Canada were finding audiences in the island’s diaspora around the world and were in turn being influenced and appreciative of African, American, and Caribbean forms.

Reggae Toronto has an incredible Facebook archive of club listings from that time which evidence the variety of venues that booked reggae in the early 80s and the overall eclectism of bookings in general. On the promoter front, Lance Ingleton and Jones and Jones created diverse Afrocentric concerts which had kinship with the emerging commercial category of world music, as “>this ticket stub‘s “upcoming shows” from Ingleton is evidence.

The 90s saw the rise of dancehall with artists like Carla Marshall, Nana Mclean, and Devon Martin’s hip hop crossover (“Mr. Metro” getting MuchMusic play) featuring digital rhythms. Toronto dancehall’s most infamous exponent was Snow, who went #1 on the Billboard charts with his nonsensical but well intentioned “Informer.” Kardinal Offishall represented a far better hip-hop/dancehall sound. Hip hop was in ascendance culturally if not exactly on an industry level and had the effect of pushing reggae out of its preeminent spot as the music of black Toronto.

Nevertheless, reggae remained in the news both in print and on the air. Reggae-friendly alternative print media now included the Toronto counterpart to Vibe magazine, Word, plus Eye Weekly and Exclaim covering reggae semi-regularly.

Phil Vassell, co-founder of Word, commented on the magazine’s music mandate, “It had to reflect reggae along with hip hop, R&B/soul, jazz, Soca, African, and Latin music. All these were music of black origin. Reggae’s deep roots in Canada, especially here in Toronto made it a must in terms of our editorial coverage.”

On the radio dial, new arrivals CHRY and especially CIUT, which broadcast live reggae from a Kensington after-hours rehearsal space for six hours every Saturday night, provided greater opportunity for airplay than greater before. Carried forward from the soundsystem era was a certain amount of kinship between “golden age” hip hop DJs and their reggae equivalents. Even Punjabi via UK bhangra found an unusually strong reception in Toronto with its ragga tendencies.

Moreover, reggae’s reach was extending through other styles of music locally and internationally. Toronto had always appreciated dub, the spacier, instrumental variant to reggae. Starting in the early 90s, dub and the new kind of double-speed breakbeat music with dub basslines from the UK started to make its mark.

The city became renowned as a major center for Jungle cum Drum and Bass. DJ Chocolate, one of Toronto’s busiest reggae selectors and radio personalities of the past 15 years, recalls “The Resinators made some pretty darn good ragga jungle with my favorite ragga jungle MC, Caddy Cad. The intersection was more obvious in terms of DJs who played both kinds of music, like Marcus Visionaryand Medicine Muffin.”

Toronto, while no Montreal in this regard, absorbed and amplified second and third waves of ska with bands like Skaface and The Skanksters. Truths and Rights’ Adrian Miller may well better be known as a ska singer than a roots reggae singer. However, the biggest exponents of reggae crossover were rock based: Raggadeath’s train wreck of hard rock and deejay Michie Mee and Big Sugar’s whisky soaked slide guitar meets estimable reggae rhythm sound made waves from coast to coast thanks to MuchMusic support.

Reggae bands during this era included Fujahtive, Revelation, Sunforce, Tabarruk, and One (fronted by Chris Taylor, now head of Last Gang) played a gradually diminishing circuit downtown including the El Mocambo, the Jerk Pit and the Bamboo. Many of these bands were multicultural, not solely Jamaican, which indicated the ever growing reach of the music through Toronto.

By the beginning of the last decade, reggae was simultaneously more international than ever and falling further from visibility within the Canadian music industry. Veterans like Willi Williams could hook up with the likes of German producers Rhythm & Sound and create stunning tech-dub records file-transferred all around the reggae world and play to packed houses in Europe and Japan, but remain unknown in downtown Toronto.

When downtown Toronto’s live music scene and label-scape was revitalized by the DIY spirit of indie-rock, the by-default historical DIYness of reggae in Toronto simply didn’t figure into this new generation (aside from Broken Social Scene’s dub excursions). It wasn’t as though the indie-rock generation wasn’t familiar or hostile towards reggae on an international or historical level, but whatever cultural integration spawned by reggae downtown in the 80s was no longer in evidence.

And yet reggae thrived on its own terms, whether through live events in banquet halls or the Jamaican Canadian Centre uptown or downtown at Holy Joe’s or Thymeless (located in the former Toronto HQ of Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association) where the SuperheavyReggae crew, Patrick Roots, and DJ Chocolate and K Zar played in classic Jamaican sound system style often with a hypeman, or in the case of SuperheavyReggae, a hornsman, playing over their rhythms.

Undoubtedly the most significant hope for reggae music on a mass market scale of the first years of the aughts was the launch of FLOW 93.5FM, Toronto’s first black-owned radio station, though it failed to live up to expectations of delivering a ‘world urban contemporary’ format. Sway Magazine, a part of the Torstar empire, launched a few years later amid similarly high hopes but ceased publication in 2012 due to low advertising revenue.

On a smaller scale, JuLion King’s Canadian Reggae World and Reggae Xclusive magazine delivered exactly as promised and both attempted to address under-representation of Toronto reggae on the web and in the Canadian music industry.

Bands, however, became rarer commodities. Dubmatix, who’d grown up counting the Jamaica to Toronto generation as family friends, remains the most successful international Toronto reggae/dub artist with his live sets which introduced a range of Toronto vocalists from Jay Douglas to Kulcha Itesto Ammoye into high tech roots productions to countless European dub festivals.

The Mountain Edge band backed up seemingly every Jamaican vocalist visiting Toronto over the past 10 years and Friendlyness and the Human Rights often opening up said shows. Singers, however, abounded: Donna Makeda, Blessed, Tasha T, LJX, and Lenn Hammond all received major acclaim in theCanadian Reggae Music Awards during the decade.

Over the last few years the most prominent news in reggae has been the demise of CKLN and founding of G98.7FM, on which Spex of King Turbo mixes and Delroy G’s Saturday show is the very definition of “big people music” for reggae fans of a certain age. The station’s constant endorsements of Sugar Daddy’s in Mississauga and Luxy in Vaughan are two of many suburban options for reggae.

Other broadcasting personalities you want to hear are Carrie (daughter of Karl) Mullings on CHRY, theMorning Ride crew on CIUT and Ron Nelson’s Reggaemania shows online. Downtown, sound crews likePressure Drop, Big Toes and Dub Connection (with its home-built system) are not Jamaican, but continue to interface with Jamaican culture (such as the upcoming Dub Connection/Pressure Drop/Tippertone Boxing Day jam).

Mullings comments that, at the Orbit Room, Lula Lounge, or the Boxing Loft, “the downtown scene presents more opportunity to see a live reggae performance – you can still enjoy an after-hours party, where the suburbs are more focused on dances and artists performances on tracks.”

Reggae is arguably stronger than ever on the festival front with the Irie Festival, Rastafest, Jamaica Day, Harbourfront’s Island Soul, and Jambana, plus, “the clash scene has never been healthier,” says Chocolate. Moreover, for years Toronto reggae and dancehall heads are well represented in every internet forum around so it`s not as though the city`s reggae history has remained isolated.

The future of reggae in Toronto is not full of optimism but neither is it threatened. Jamaican culture is a huge, even normative, part of Toronto (“true dat” you might say as you argue what truly are the best patties in the city). Two-time Juno winner Exco Levi provides hope for the future.

Adept at both roots and dancehall, he, unlike almost the vast majority of other Jamaican-Canadian artists over the decades, has enjoyed considerable success in the mother country, breaking down a historical barrier. It must be noted that Last Gang has released reggae/dancehall discs (O’Luge & Terry Lynn with K-OS and Tre Mission being reggae allies), the highest-profile label to do so in more than 25 years.

Reggae’s lack of huge sales in Canada means that at least one can’t say that reggae in Toronto has been co-opted and whitewashed. Reggae accepts contributions of people from many walks of life, and for those people Jamaica`s culture and history is the centre of their art. Toronto’s reggae history may not be as commercially and internationally renowned as its cousins around the world but there is no writing a history of Toronto music over the past 40 years without it.

And then there’s Magic who came out of nowhere to score a #1 single this year.