By Brent Clough—-

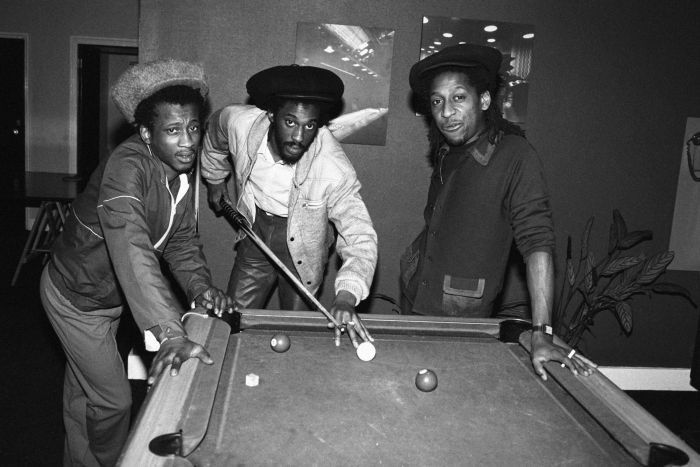

(BRINSLEY FORDE, TONY ROBINSON AND ANGUS GAYE) PICTURED IN 1984. (HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES)

In the 1980s, the South London suburb of Brixton stood as a symbolic frontline for migrants from the Caribbean, plagued by riots, unemployment and racism.

Brent Clough recently revisited his old stomping ground and discovered the home to British reggae royalty had changed dramatically.

In the early 1980s I was a young music-loving Antipodean beginning my pilgrimage to the so-called mother country. If my gran was about as loyal a colonial subject as Queen Elizabeth could hope for, my own Anglophilia was activated by rather less traditional figures.

Bands like Black Slate, Matumbi, Aswad and Steel Pulse and the brilliant dub poet, Linton Kwesi Johnson were members of my British reggae royalty.

Social injustice was a matter of policy as a way of getting out of that economic crisis. And… police harassment and oppression of black youth were the biggest issues within our communities—Linton Kwesi Johnson

These artists were part of a generation of Caribbean migrants and British-born youth who took Jamaican music and made it vital in its new setting.

They used music to address questions of black identity and struggle in a society where a leader like Margaret Thatcher could say, ‘The moment the minority threatens to become a big one, people get frightened’.

The decision, not long after arriving, to take lodgings in Brixton was driven by the understanding that this South London suburb remained a hotspot for reggae.

I was told that Harlesden in northwest London was reggae headquarters, but Brixton stood as the symbolic ‘frontline’, one of the first places migrants came to after arriving from the Caribbean.

Although black people had been in Britain in significant numbers before the Second World War, it was the 1948 arrival of the MV Empire Windrush that ushered in large-scale migration from the West Indies.

These pioneers were lured by offers of employment in sectors desperately needing willing workers.

They arrived expecting at least some sort of welcome. What most received was grudging acceptance if not outright hostility and racist violence. The Notting Hill ‘Teddy Boy’ riots in 1958 were a lesson to many black people to expect the worst as big mobs of white youth attacked them and their houses.

I knew by going to stay in Brixton in 1982 I was entering a neighbourhood squeezed by bad housing and unemployment and which only months before had been convulsed by a major riot.

After a January 1981 fire (suspected to be arson) in nearby New Cross in which thirteen young black people died, tinder-dry community resentment was exacerbated by arbitrary police use of stop and search powers—the infamous Sus Law—that allowed for the arrest of anyone deemed to be acting suspiciously.

By 10 April 1981 a street tussle between cops and bystanders over a stabbed youth escalated into a night-long uprising which left hundreds of police and protestors wounded, cars and shops burned, dozens arrested and a precedent for civil insurrection set in urban centres around Britain for months and years to come.

My first glimpse of Brixton as I stepped out of the tube station included an armoured personnel vehicle rolling down the High Street.

No moment in my subsequent stay matched that for drama, save perhaps for the kidney-shifting sound of the Sir Coxsone sound system when it dropped a particularly heavy reggae ‘riddim’ in a dance.

Sound systems replicated the Jamaican model—basically huge mobile discos with live entertainers rhyming or singing on the mic. ‘Sounds’ were central to black life in the UK in the 80s. As Linton Kwesi Johnson said of their earthquake power, they would shake ‘down your spinal column/a bad music tearing up your flesh’.

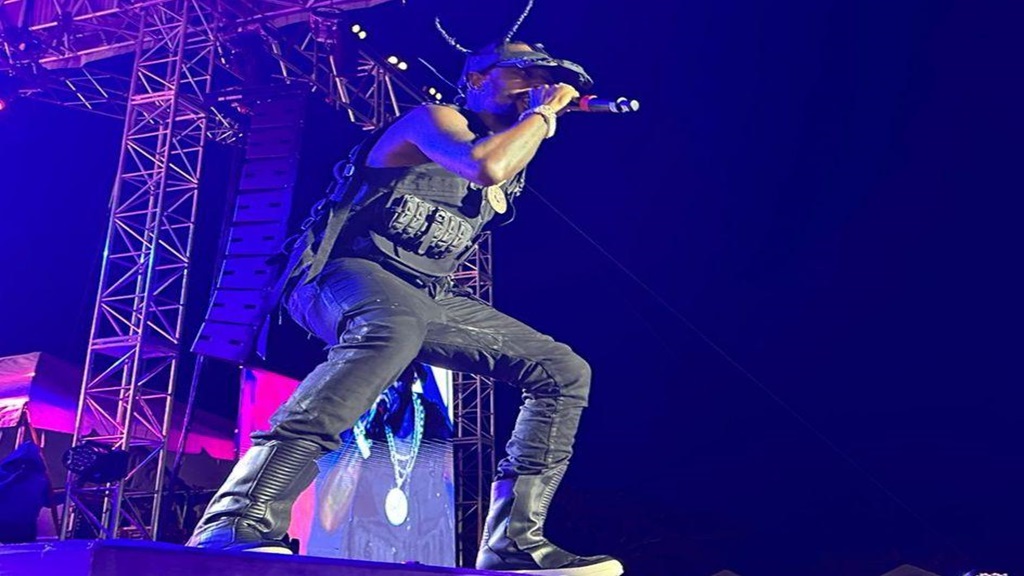

I was joyfully concussed by a few sounds during my stay—large sets like Sir Coxsone and smaller rigs playing local parties. I went to reggae pubs, clubs, and concerts (the mighty Aswad at the Brixton Ace a special highlight). I never felt unsafe, but I chose my routes after dark.